Mountainous Fails: Tales of Overconfidence, Altitude, and a Humbling Lack of Coordination

Reading time: About 10 minutes.

How often does a regular person need help getting off a mountain? Once in a lifetime, maybe? It’s understandable if it’s once. But twice? Twice starts to sound like a hobby.

And yet, I—a fairly average person by most measures—have managed to require mountain rescue twice. Not because I live a rugged, outdoorsy life but because I think I’m more rugged and outdoorsy than I actually am, so I head up the slopes with the confidence of a sherpa.

“The Full 360”

The first time I needed help getting off a mountain was when I was 17, that magical age when you believe you're indestructible. Back then, I threw myself into downhill skiing with the reckless abandon of someone blissfully unaware of future medical bills. My skills were what you might generously call “intermediate,” but I had pluck. And when you're 17, pluck feels like all you need. That, and gravity.

The look of a girl waiting in line for her ski gear who has no conception of her mortality.

The last clear memory I have of that day is flying down the slope at a speed that can only be described as "too fast to stop and not fast enough to achieve liftoff." I was out of control, and I knew it. The mountain was crowded, so I prayed—not to avoid a fall, but to avoid taking anyone else out with me.

Thank goodness I wasn’t skiing alone. My sister Jessie and my brother from another mother, Mark, were on the mountain too. We had taken the ski lift together, but our safety thresholds differed. They took things at a normal human pace, meandering down the mountain on an s-curve with a perfect pie-wedge stance. I, on the other hand, pointed my skis downhill like a demon with a death wish and went pedal-to-the-medal parallel.

According to Jessie and Mark, what happened next was a blur of Olympic-level acrobatics. I hit a mound of snow and suddenly became a human snowball, tumbling down the slope in what they described as "several full 360s." My skis, poles, sunglasses, and a major chunk of my dignity scattered across the mountain. When I finally came to a stop, I sprang to my feet, arms raised in victory, and declared, “That was a perfect ten!”

It was not a ten.

Jessie, Mark, and a handful of kind strangers skied up to me with the belongings I had littered across the mountain. Everything seemed normal as I put my skis back on, but all the color rushed out of my cheeks when I stood up and turned to my sister. Instead of joking around, I started asking the same questions over and over, like, “Where are we?” and “What day is it?”. Jessie looked at Mark, Mark looked at Jessie, and then they both looked at me, realizing one of my circuits had popped. Things were suddenly serious.

“Crested Butte,” Jessie said. She spoke slowly, enunciating like a negotiator in a hostage situation. “It’s Tuesday. We’re on spring break in Colorado.”

The church ski trip. Right. A wholesome activity designed to bond us with God and nature—or, in my case, with a medic on a jet ski. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

A postcard my dad sent to my grandmother during our trip.

Mark spotted our parents preparing to board a ski lift, so he raced off as fast as his legs could take him, shouting their names. “EDITH! ANTHONY!” he bellowed, waving his arms as if he were trying to flag down a lifeboat on a sinking ship. My parents, unbothered, smiled and waved back as they ascended, probably assuming he was excited to see them on the same slope.

Meanwhile, Jessie and Mark had to figure out how to get me—conscious but clearly confused—onto the ski lift so we’d have a chance to meet up with them. This involved sandwiching me between them like peanut butter and jelly slapped together by someone who forgot the bread. As soon as they answered one question, I asked another in an endless cycle: “Where are we? What day is it?” I have no doubt they continued to answer me with a level of patience that required divine intervention.

By some miracle, my parents were waiting for us at the top of the lift. Mark’s heroic theatrics had not been in vain. There was a medic shed nearby, so my family ushered me toward it. My condition was bad enough that the mountain medics determined I needed to be seen by the doctors at the base. The only way to get me down there was via a rescue jet ski. (I should clarify. It was a snowmobile. But we always called it a jet ski, which somehow made it sound cooler.)

According to my mom, a "gorgeous young man" piloted the vehicle, and I had to wrap my arms around him for the ride. She relayed this detail with such wistfulness you'd think she had been the one concussed. Sadly, I remember none of it. Happily, though, my injury was pronounced as “merely a concussion,” and soon, I was back under the worried and watchful eyes of my parents. I spent the rest of the day alternating between napping and repeatedly asking the same questions, turning my poor mother into a broken record stuck on the world’s most irritating loop.

The good news? It was just a concussion and some bruises. The bad news? My days of carefree skiing were over. I have since returned to the slopes, but now I’m the human embodiment of “safety first.” No more speed demons, no more 360s. It’s paralyzing. I’ve traded youthful recklessness for middle-aged terror.

And as for the second time, I needed help off a mountain? Let’s just say old habits die hard.

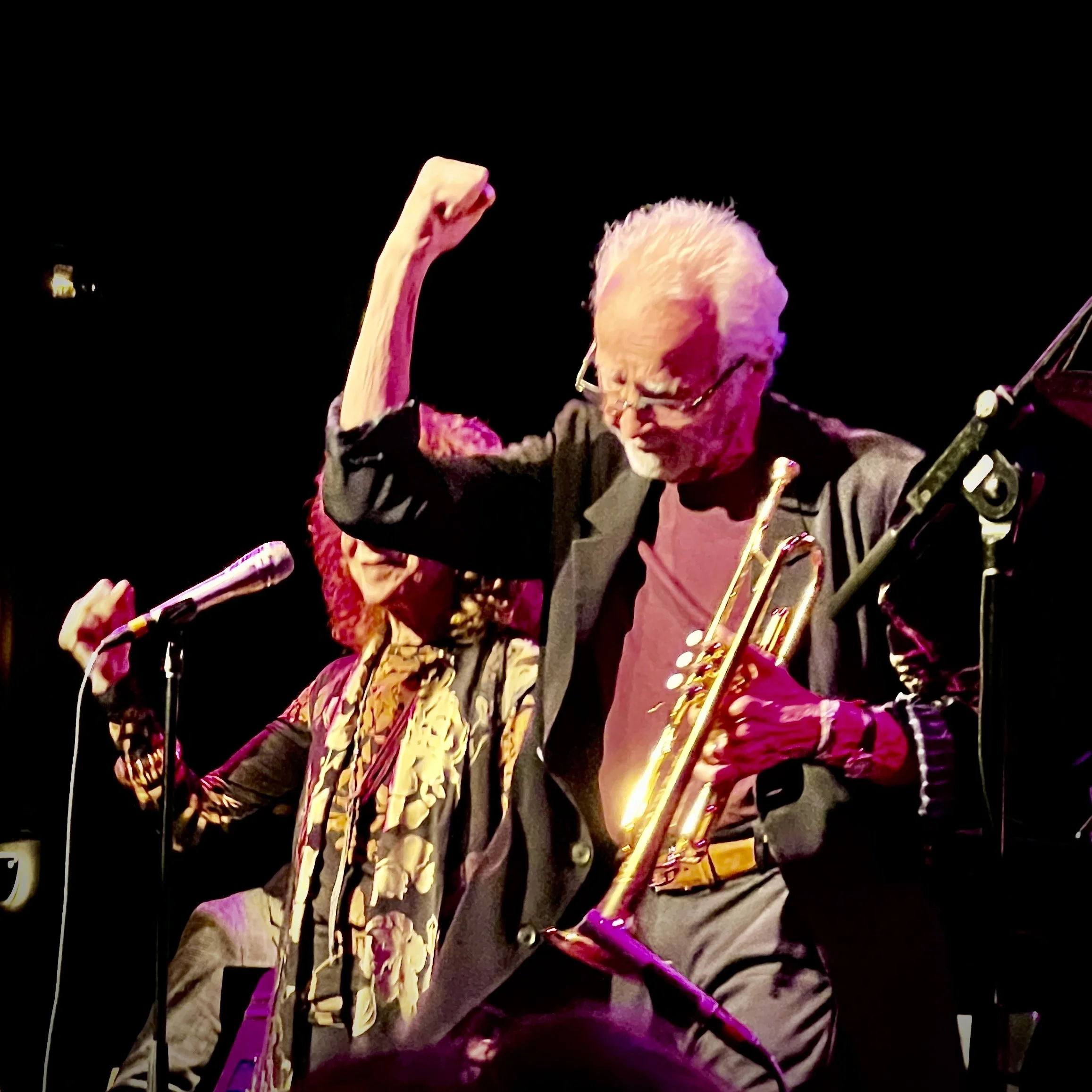

The heroes of the hour—Mark in the center of the photo in the red jacket, and Jessie on the far right in the white jacket.

Snowshoes Don’t Protect You from Altitude Sickness

You’d think that after 36 years, I’d have learned to stay off mountains. But no. Not only did I find myself on the side of another one, I did so willingly, in snowshoes no less—because I apparently like my humiliation accessorized.

Snowshoes, if you’re unfamiliar, are the anti-skis. Where skis are sleek and fast, snowshoes are clunky and slow, with metal teeth that scream, “We will not let you fall!” Which is why I picked them. I wanted a safe, sensible adventure, the snow-sport equivalent of wearing a helmet while walking.

So, when my dad and sister visited last February, I signed us up for a snowshoeing excursion on Mount Rainier with Evergreen Escapes.

All smiles as we headed up the trail.

Nothing about the morning hinted at doom. Sure, the 8:30 a.m. pickup was a personal affront to someone who proudly considers herself a night owl, but I compensated with enough coffee to power a small electric generator. Besides, I was determined to make this trip memorable—in a good way, not the “remember when Sherry had to be carried off a mountain” way.

From the moment we strapped on our snowshoes in the visitor center parking lot, I assumed my role as leader. I wanted my dad and sister to feel safe. I wanted them to feel they were in good hands. Never mind that I couldn’t figure out how to tighten the straps properly—I faked confidence like my life depended on it.

Once we hit the trail, I felt that electric rush of joy and the totally unjustified confidence I’d felt as a 17-year-old on skis. The snow sparkled in the sunlight, and I suddenly understood why Julie Andrews twirled around singing on mountaintops. When my dad tipped over into a pile of powder, I offered him my hand like some benevolent deity. Think Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam.

Pride, as they say, comes before a fall. And what a fall it was—though, thankfully, not the kind I had in Crested Butte in 1988.

We trudged up the trail until we reached a ridge with views so spectacular they could’ve been postcards. Our guide, Marty, gestured toward a slope and announced our goal: a waterfall “just over that way.” The mountain seemed empty except for us, which felt thrilling and ominous in equal measure.

While the group moved on, I lingered to take photos, basking in the grandeur and imagining how much my husband would love this. At that moment, I felt invincible. Sure, the mountain could squash me into a human snow cone if it wanted to, but I was certain it wouldn’t. Mountains have standards.

Then the wind picked up, and the sun disappeared behind the clouds. With it, my hubris took a nosedive. Maybe mountains don’t have standards?

It started with my hands, which I realized were numb after taking off my gloves. My face followed. My top lip felt swollen to cartoonish proportions. The once-sparkling snow turned into a stinging blur. The Arctic gusts whipped my hair into tiny, frozen dreadlocks. I chugged up the hill and caught up to the group, but everything felt off. I tried to dismiss it, but when I looked down at my feet, they looked like someone else’s, and the trail ahead tilted in ways it shouldn’t. Was I about to pass out? I think I was.

“Um, guys. I need a minute,” I said, squatting down. Squatting felt less defeatist than sitting. Plus, I didn’t want to get my pants wet with snow. Wet pants could mean dangerously frozen pants.

Marty clomped toward me with the no-nonsense air of a man who’s seen this before. “Altitude sickness,” he announced. “Happens to the best of us.”

While this diagnosis may have been intended to comfort, it only added insult to injury. Altitude sickness? For me? I’d hardly earned it. We were barely over 5000 feet above sea level, not scaling Everest. I was just a middle-aged woman on snowshoes out for a day with my family. Still, I accepted the granola bar he offered, but it turned into a paste in my mouth.

Struggling to get the granola bar down only made me panic more, so I gave up squatting and dropped flat to the ground, legs splayed out in front of me. There I was, paralyzed by cold, nausea, and the fear of wet pants. I didn’t know how I was going to get back down the hill, but when Marty mentioned the possibility of retrieving a tarp to fashion a makeshift gurney, I was shocked into action. The idea of being carried down the mountain was simply too much.

With Marty and Dad’s help, I managed to stand, though I moved with all the grace of a rusty wind-up toy on its last turn. I focused on putting one foot in front of the other, refusing to look at anything except the trail. Somehow, I stumbled my way back to the van, where I collapsed in a soggy heap.

The warmth didn’t hit immediately, but the wet pants sure did. I shivered uncontrollably as Jessie wrapped me in her jacket and rubbed my back. (Pro tip: always pack a Jessie.)

An hour and a warm lunch later, I was still frozen solid, but I was functional again. The whole ordeal left me shaken, though. Mountains, it seems, are not my natural habitat, no matter how many layers of quilted jackets and ill-conceived confidence I pile on.

What stands out to me now about both of my mountain misadventures isn’t just the physical toll but the lesson in humility. Each time, my ego wrote checks my body couldn’t cash. Luckily, I’ve always had people—family, friends, or strangers—ready to help when I was flat on my back.

Still, maybe I should stick to sea level from now on. Or at least bring better pants.

Marty managed to get this photo on the way down. You’d never know from this photo that I felt like I was going to throw up all over him.