Teilhard’s Noosphere: The Internet Before the Internet

A Jesuit scientist envisioned a planetary mind a century ago—but he didn’t see everything coming.

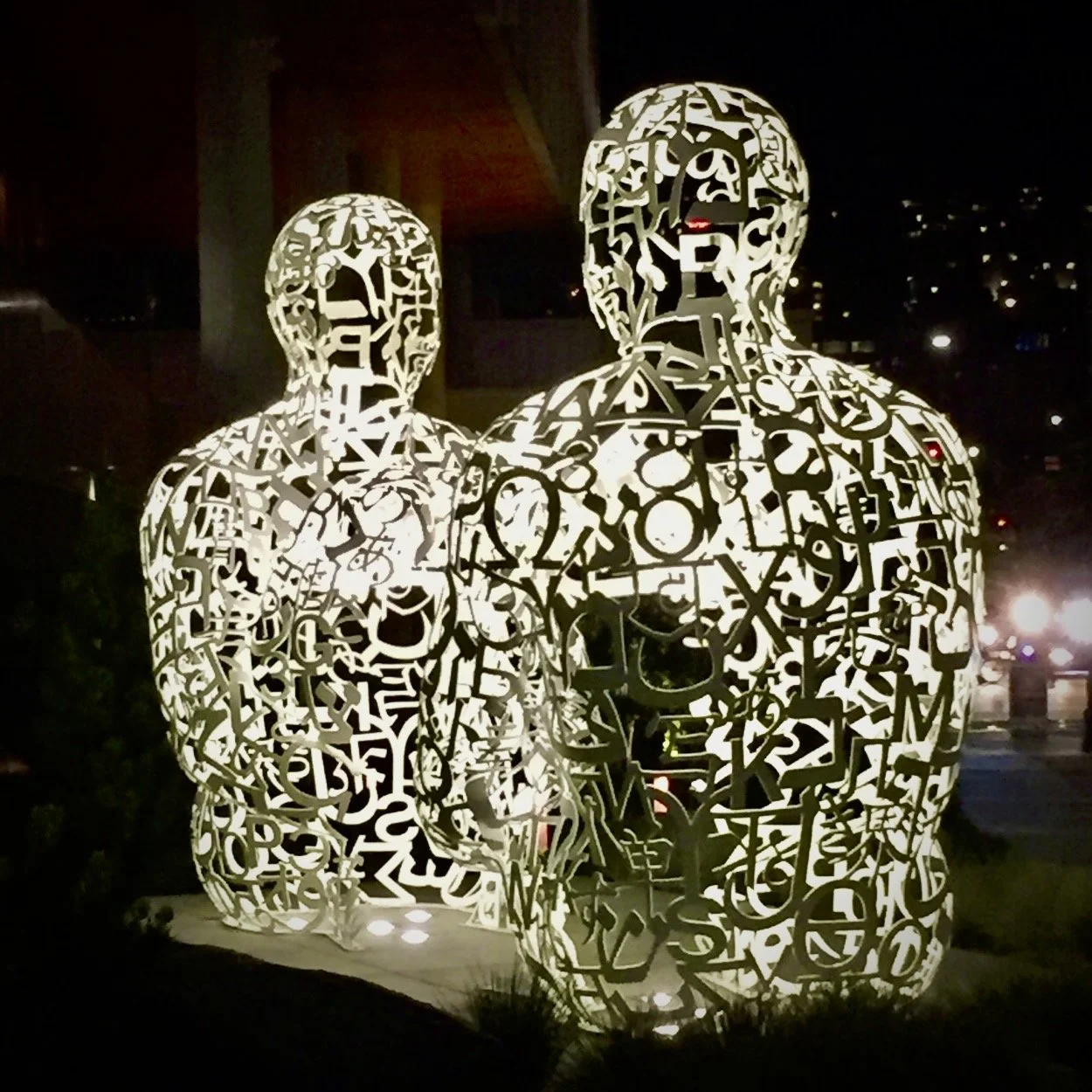

Mirall by Jaume Plensa. Photo by me. These intriguing statues are public art outside The Allen Institute in Seattle.

This is part of a series exploring Teilhard de Chardin’s radical vision of the Noosphere—an interconnected planetary mind he believed would shape the future of humanity. A century later, we’re living in something that looks an awful lot like it… but not exactly how he imagined. Each piece stands on its own, but together, they ask a crucial question: Who controls the Noosphere now—and how do we take it back?

You’ve Got Mail… and a Future Husband?

The first time I heard the screech of a dial-up modem, I had no idea it would change my life.

At the time, I wasn’t even sure it was supposed to sound like that. The chaotic symphony of beeps and static made me briefly wonder if I was summoning a demon. But no—just the Internet. Which, in the long run, might be more powerful.

It was the early days of the web. I was living in a basement apartment in Rockville, Maryland, working as a nanny, and trying to figure out what to do with my life. A year earlier, I had graduated with a degree in advertising, only to realize the industry required a level of cutthroat ambition I did not possess.

So, naturally, I floundered.

Then, my parents gave me an Apple IIGS, and suddenly, the floundering had a soundtrack: the digital screeches of America Online.

I logged in, found my way to writers’ chat rooms, and felt like I had discovered a new world—one where people weren’t just making small talk but actually writing. Tossing around ideas. Creating. Connecting.

And then, the men arrived.

This was my first real taste of an enduring Internet truth: If you are a woman in a public space, you will be hit on.

I wasn’t there to flirt. I was there to write. But the moment I logged in, my inbox filled with messages from strangers. Some subtle (“Hey, what are you working on?”), some not (“Hey, what are you wearing?”).

It was exhausting.

So, I started blocking people. Not today, creepy Internet men.

And then, one night, Mike logged on from Minneapolis.

Unlike the others, he didn’t open with a pickup line. He asked about my screen name. It included the name Sabine (a book character I liked), and he was curious. The only Sabine he had ever known was from Haiti—was that where I was from?

At first, I ignored him.

Then, I ignored him again.

But he kept showing up—not pushy, not intrusive, just… genuinely interested in conversation. One night, I answered.

And suddenly, we were talking. Not just surface-level chatting, but real talking.

That one conversation turned into another. And another. Before long, we were exchanging long, sprawling emails—the kind that feel like letters, the kind where you pour out your thoughts without worrying about how they’ll be received.

Then, one day, he asked if he could fly to Maryland to meet me.

I said yes.

A few months later, I packed up my life and moved to Minneapolis. A year after that, we were married.

Looking back, it all seems improbable—two people, from different cities, different lives, somehow finding each other in a messy tangle of early Internet connections.

And yet, according to Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, this wasn’t just luck.

It was part of something bigger.

Teilhard had a name for it:

The Noosphere.

Teilhard’s Wild Idea: A Thinking Layer Around the Earth

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin was a French Jesuit priest-paleontologist, which is an almost comically rare job title.

Teilhard had a radical idea: evolution wasn’t just about biology. It was about consciousness.

He believed that as human thought became more complex, it was forming a kind of planetary intelligence—a vast, interconnected web linking all minds together. He called this the Noosphere (from the Greek noos, meaning “mind” or “intellect”).

But Teilhard wasn’t just talking about better communication. He believed the Noosphere was something fundamentally unique to humans.

See, animals inherit everything they need to know through instinct. A beaver isn’t born wondering how to build a dam—it just knows. Every beaver, everywhere, instinctively understands how to be a beaver.

Humans? Not so much.

We don’t come into the world already knowing how to do calculus or bake bread or perform open-heart surgery. Everything we know, we learn—from books, from teachers, from each other. And the sheer volume of human knowledge is so vast, so sprawling, that no single person could ever hold it all.

The Noosphere, then, wasn’t just a metaphor for connection. It was Teilhard’s way of explaining how human knowledge accumulates, expands, and evolves over time. A collective intelligence, passed from one generation to the next, constantly building on itself.

And Teilhard believed this wasn’t just an interesting quirk of our species—it was our evolutionary destiny.

The Noosphere, he argued, was just as real as the biosphere (the layer of life) or the atmosphere (the layer of air). It was a living network of human knowledge, shaping our future.

This was in the 1920s.

The Internet would not exist for another half-century.

Teilhard wasn’t just predicting better communication tools. He was predicting a world where human minds were linked, where ideas spread instantly, where knowledge was collective.

Sound familiar?

Teilhard basically predicted the Internet.

Except…

He got a few things very, very wrong.

Teilhard’s Blind Spot—The Contradiction at the Heart of His Vision

Teilhard believed humanity was evolving toward greater unity, greater consciousness.

But here’s the problem: he didn’t think that unity applied to everyone.

For all his radical ideas about interconnectedness, Teilhard was deeply entrenched in racist, colonialist thinking.

He believed in a hierarchy of people—that some races were more evolved, more deserving of progress than others. And—this is where it gets real uncomfortable—he entertained eugenics.

Teilhard preached love as the force pulling the universe forward.

But he excluded entire populations from that vision.

And once you see that contradiction, it’s impossible to unsee.

Teilhard dreamed of human consciousness expanding toward a better future.

But he never asked: Who gets to be part of that future?

He never stopped to consider that the people he dismissed—the ones he saw as less “evolved”—might have perspectives that could have changed his own understanding of the Noosphere.

Teilhard was exiled by the Church for his views on evolution.

Did he ever stop to consider who else had been exiled?

Not for their ideas, but for their existence?

Who Controls the Noosphere Now?

This brings us to the present day, where Teilhard’s ideas have been picked up by people I want absolutely nothing to do with.

Transhumanists. Silicon Valley technocrats. Elon Musk.

These are the people who see Teilhard’s Omega Point not as a metaphor for human connection but as justification for their own dominance—a world where technology, AI, and genetic engineering decide who is worthy of evolution.

Teilhard’s own flirtation with eugenics makes his work far too easy for these people to claim.

But I refuse to let them have it.

Because Teilhard was wrong about many things—but the idea of the Noosphere, a shared human consciousness shaping the future, is bigger than him.

Bigger than Musk.

Bigger than transhumanism.

Bigger than the narrow, elitist vision of progress that excludes so many.

So if we are to take Teilhard’s vision seriously—if we are to imagine a Noosphere worth fighting for—we have to expand it beyond his limitations.

We have to reclaim it.

Because if the Noosphere isn’t for all of us—it isn’t progress at all.

Final Thoughts

Teilhard glimpsed something extraordinary.

But he couldn’t see the whole picture.

Maybe that’s the whole point of the Noosphere—that no one person can.

It’s not about a single visionary.

It’s about all of us.

And what we do with it—that’s up to us.